The theme of Earth 2021, Restore Our Earth, is a call to action to do more to address the climate crisis and restore our remaining fragile ecosystems, through both natural processes and technological and social innovation.

Dr. Tracey Heatherington, associate professor of anthropology at UBC, is an environmental anthropologist whose research focuses on the political ecology of nature conservation. She studies biodiversity initiatives, such as the Svalbard Global Seed Bank in Norway. We spoke with Dr. Heatherington about her research on the role of science, technology and social institutions in addressing climate change and supporting more sustainable agriculture — and how humanities thinking can help set us on the right course.

Post Archive “View More” test

What is the Svalbard Global Seed Bank and what sparked your interest in studying it?

Svalbard is a back-up system for major seed collections around the world, which are like living libraries of the biodiversity needed for agriculture. The vault in Svalbard keeps samples for other seed banks, in case something happens to one of them, like the tsunami in the Philippines that destroyed some collections a few years ago, or the war in Syria. The scientists at the ICARDA seed bank in Syria stayed as long as they could to back up pretty much everything at Svalbard, before they had to cease operations. Because of those efforts, they were able to get the seeds to re-establish the working collections, after moving operations to another location. I was able to view the boxes of seeds from ICARDA at the Global Seed Vault in 2015.

This is an example of 65 characters in use for the title section

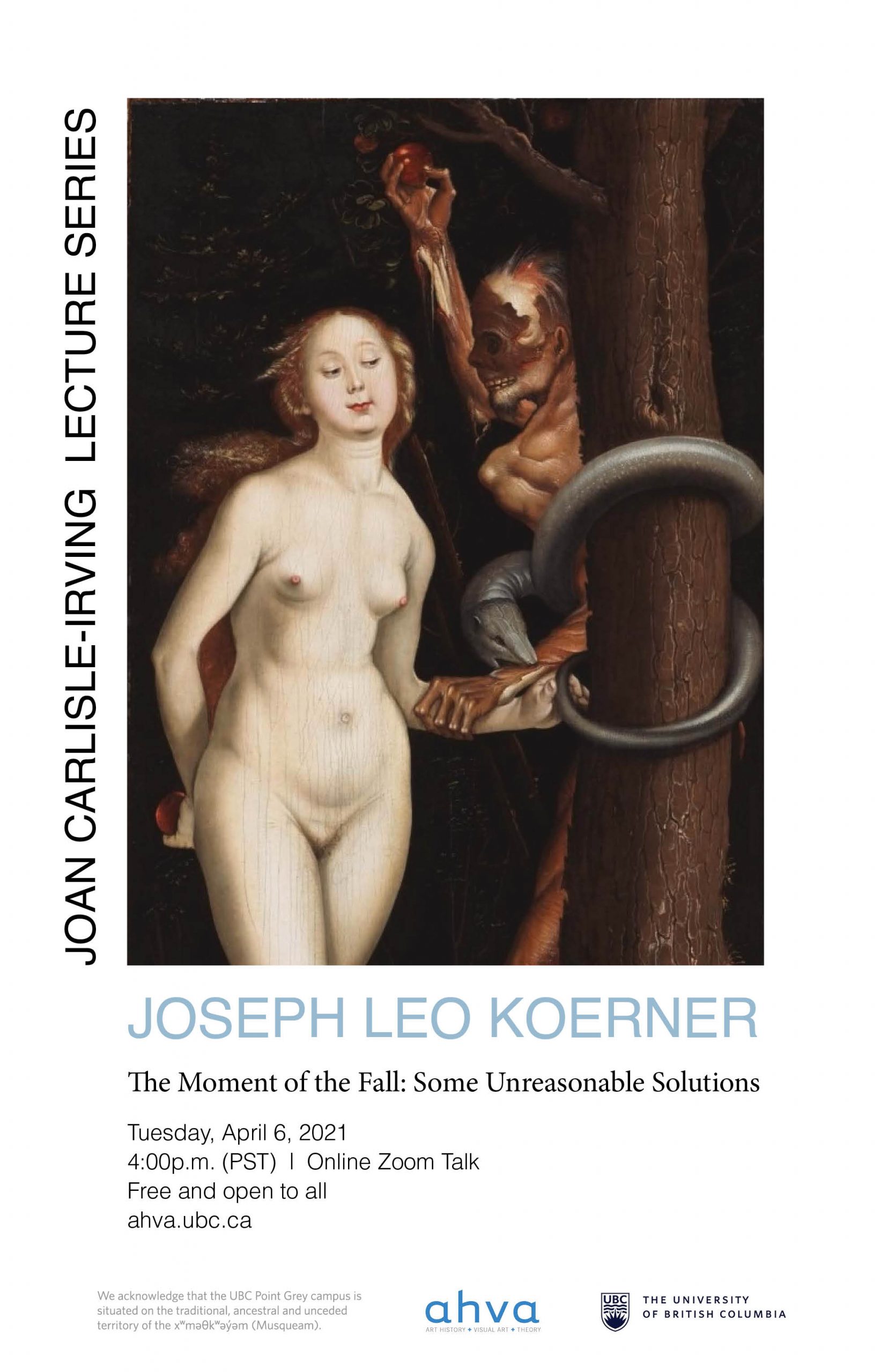

Joseph-Koerner-Lecture-Poster-2021-scaled

This is an example of 65 characters in use for the title section

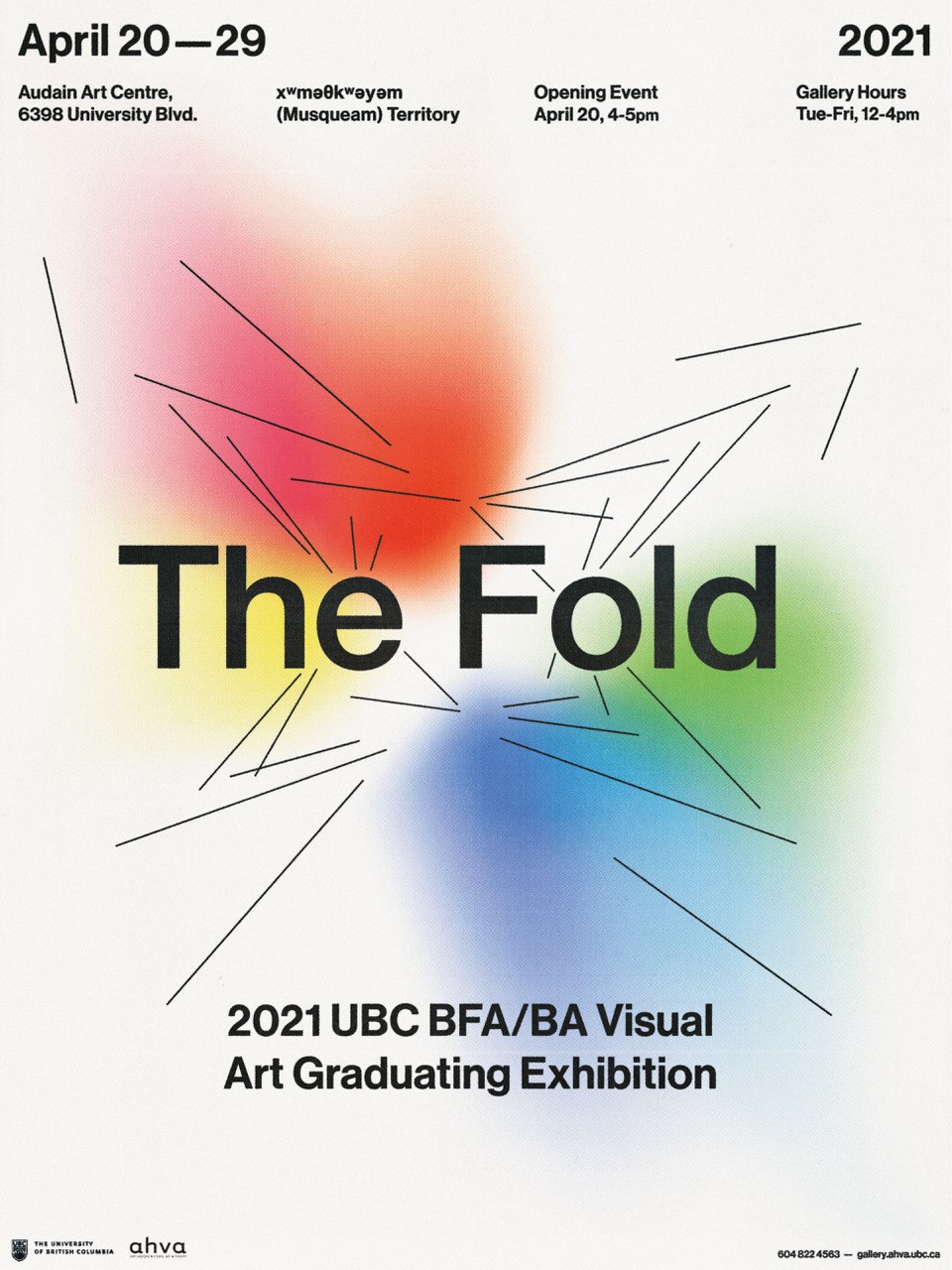

The-Fold-Updated-Poster-min-1

This is an example of 65 characters in use for the title section

Undergraduate-Carousel-UBC-AHVA

This is an example of 65 characters in use for the title section * This is an example of 65 characters in use for the title section

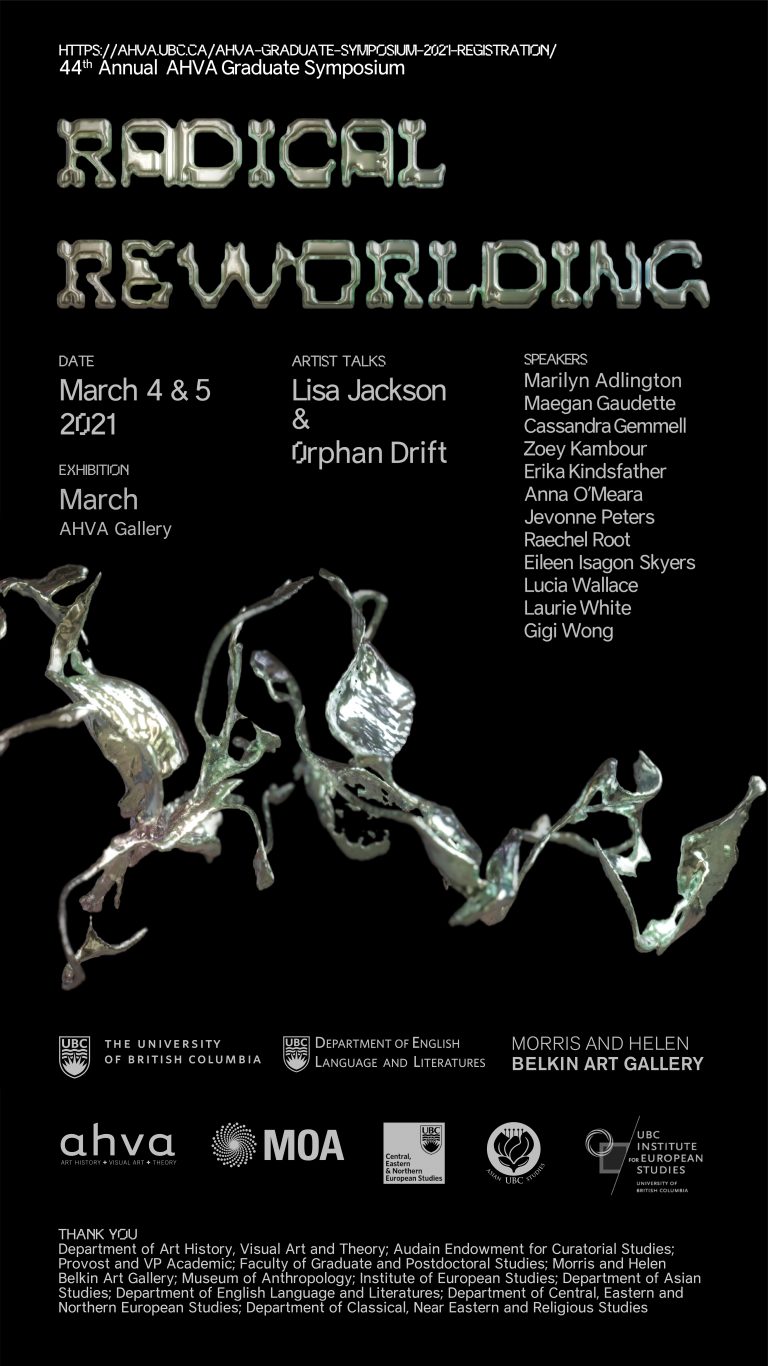

Symposium-Poster-FINAL-768x1366

vsaranphotodotcom-WEB-62-content

rawpixel-com-589076-unsplash

Caption 3

38906346260_191f79bf9e_z

pexels-photo-1325733

WerkerKillamReduced

DSC_0178-300x199

cropped-HR-Antje-Ellermann-2

Susan-Rice-275x300

Susan Rice

39987113034_37e1b3fb42_z

vsaranphotodotcom-WEB-62

cropped-GhazianiA_3

As an environmental anthropologist, I am interested in how we collectively imagine the role of science, technology and social institutions in addressing global climate security. My research focuses on initiatives for biodiversity conservation, so seed banks are quite intriguing.

2-Portrait

1-Portrait

3-Landscape

2-Landscape

I think the whole world was fascinated when the Svalbard Global Seed Bank opened in 2008, and every year when new deposits are made, it helps open different cultural visions of the past, present and future of agriculture. For example, when Kenyan environmental activist Wangari Maathai brought seeds from African Rice to the vault in 2008, and the Cherokee Nation deposited its own seeds in 2020, it was deeply evocative. The heritage seeds in the vault have particular cultural histories, and today, many are still living components of the communities in which they evolved. It matters how we shape our laws and institutions to protect these multispecies communities.

3-Landscape

2-Landscape

3-Portrait